- Submit a Protocol

- Receive Our Alerts

- Log in

- /

- Sign up

- My Bio Page

- Edit My Profile

- Change Password

- Log Out

- EN

- EN - English

- CN - 中文

- Protocols

- Articles and Issues

- For Authors

- About

- Become a Reviewer

- EN - English

- CN - 中文

- Home

- Protocols

- Articles and Issues

- For Authors

- About

- Become a Reviewer

Isolation and Culture of Human CD133+ Non-adherent Endothelial Forming Cells

Published: Vol 6, Iss 7, Apr 5, 2016 DOI: 10.21769/BioProtoc.1772 Views: 11497

Reviewed by: Ningfei AnThomas J. BartoshAnonymous reviewer(s)

Protocol Collections

Comprehensive collections of detailed, peer-reviewed protocols focusing on specific topics

Related protocols

Identification and Sorting of Adipose Inflammatory and Metabolically Activated Macrophages in Diet-Induced Obesity

Dan Wu [...] Weidong Wang

Oct 20, 2025 2227 Views

Selective Enrichment and Identification of Cerebrospinal Fluid-Contacting Neurons In Vitro via PKD2L1 Promoter-Driven Lentiviral System

Wei Tan [...] Qing Li

Nov 20, 2025 1335 Views

Revisiting Primary Microglia Isolation Protocol: An Improved Method for Microglia Extraction

Jianwei Li [...] Guohui Lu

Dec 5, 2025 1453 Views

Abstract

Circulating endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) have been the focus of many clinical trials due to their roles in revascularisation following ischemic events such as acute myocardial infarction as well as their contribution to vascular repair during organ transplantation. Research on EPCs has been controversial due to the lack of distinct markers expressed at the cell surface and varying methods for isolation and culture have resulted in the identification of a multitude of cell types, with differing phenotype and function, all falling under the label of “EPCs”. The most widely documented EPCs isolated for cell therapy are adherent in nature and lacking the progenitor markers such as CD133 and therefore unlikely to represent a true circulating EPC, the cells mobilised in response to a vascular injury.

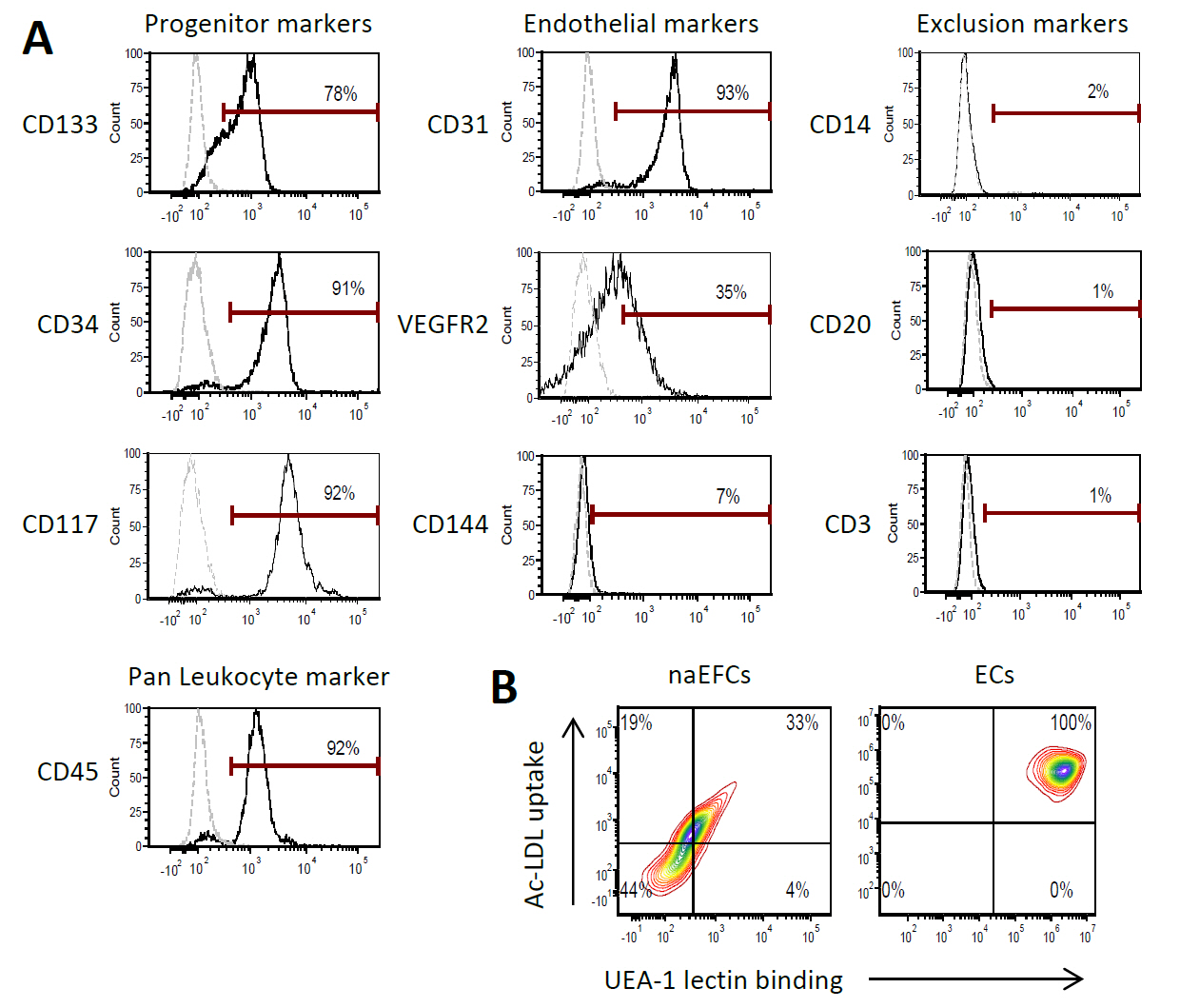

We recently published the isolation and extensive characterisation of a population of non-adherent endothelial forming cells (naEFCs) (Appleby et al., 2012) (Figure 1). These cells expressed the progenitor cell markers (CD133, CD34, CD117, CD90 and CD38) together with mature endothelial cell markers (VEGFR2, CD144 and CD31). These cells also expressed low levels of CD45 but did not express the lymphoid markers (CD3, CD4, CD8) or myeloid markers (CD11b and CD14) which distinguishes them from ‘early’ EPCs, the ‘late outgrowth EPC’ [more recently known as endothelial colony forming cells (ECFCs)] as well as mature endothelial cells (ECs). Figure 2A exemplifies the surface expression profile of the naEFCs. Functional studies demonstrated that these naEFCs (i) bound Ulex europaeus lectin (Figure 2A), (ii) demonstrated acetylated-low density lipoprotein uptake, (iii) increased vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM-1) surface expression in response to tumor necrosis factor and (iv) in co-culture with mature ECs increased the number of tubes, tubule branching and loops in a 3-dimensional in vitro matrix. More importantly, naEFCs placed in vivo generated new lumen containing vasculature lined by CD144 expressing human ECs and have contributed to various advances in scientific knowledge (Appleby et al., 2012; Barrett et al., 2011; Moldenhauer et al., 2015; Parham et al., 2015). Here, we describe the isolation and enrichment of a non-adherent CD133+ endothelial forming population of cells from human cord blood.

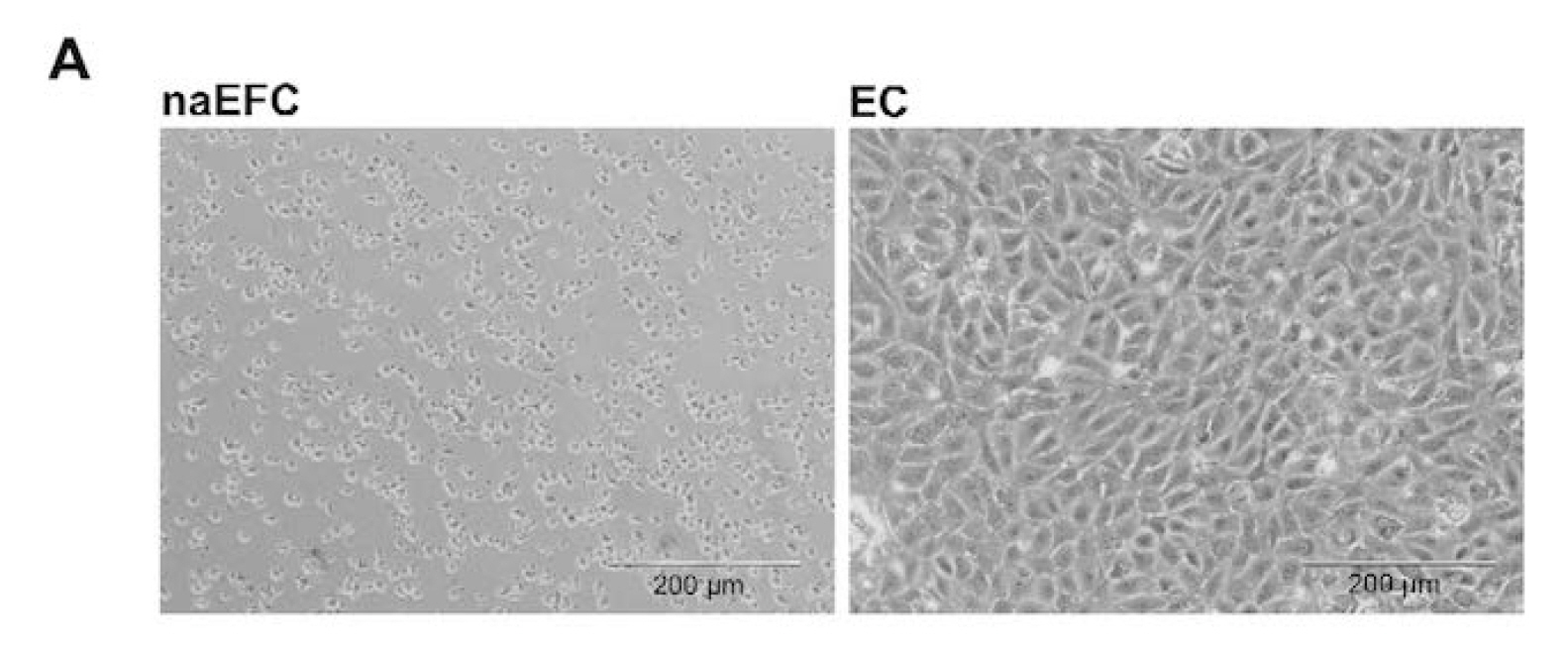

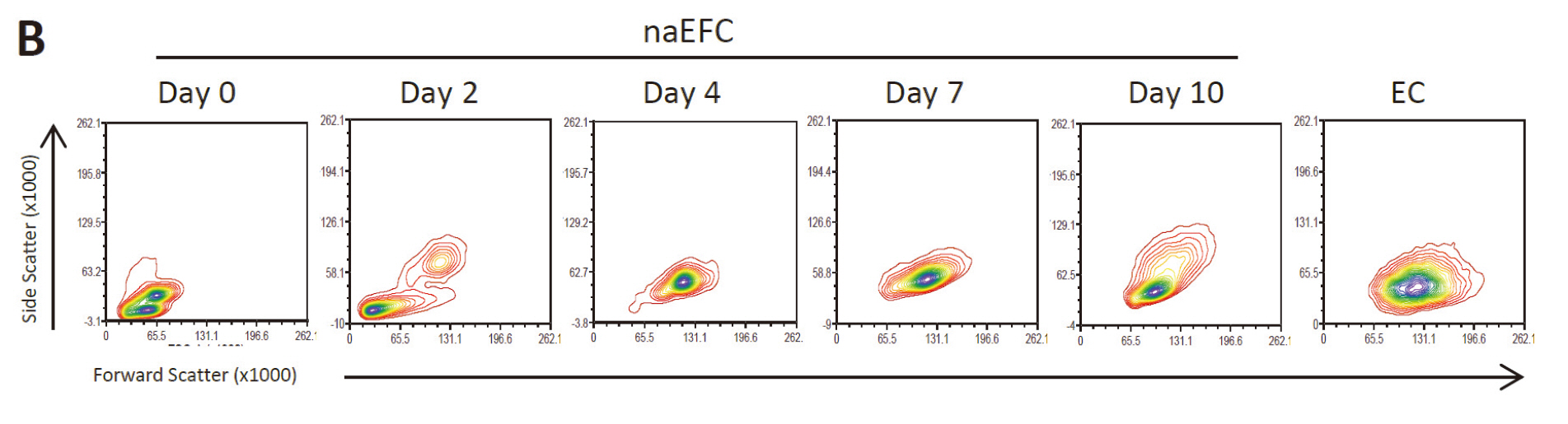

Figure 1. Enrichment of human naEFCs. A. Umbilical cord blood derived CD133+ enriched cells (naEFCs) at 4 days of culture and human umbilical vein endothelial cells (ECs) were compared for cell size by light microscopy. Scale bar=200 µm B. The cells were assessed for heterogeneity of enrichment process (0-10 days) via forward scatter and side scatter profiling using flow cytometric analysis and compared to mature ECs.

Figure 2. Surface expression phenotype of human naEFCs. A. CD133+ enriched cells at 4 days of culture were assessed for progenitor and endothelial markers by flow cytometry. Histograms show a representative experiment from ≥3 biological replicates where grey dashed lines represent isotype controls and solid black lines represent cells stained with the indicated marker. B. The function of the naEFCs was assessed by flow cytometry and compared to mature ECs, detecting the ability of cells to uptake DiI labelled acetylated low density lipoprotein (Ac-LDL) and bind FITC labelled Ulex europaeus agglutinin I (UEA-1) lectin. Density plots represent stained cells of one representative experiment from ≥3 biological replicates.

Materials and Reagents

- For manual cell sorting

MS Columns (Miltenyi Biotec, catalog number: 130-042-201 ) - MacoPharma cord blood collection bags (MacoPharma, catalog number: MSC1201DU )

- 50 ml tubes (Corning, Falcon®, catalog number: 352070 )

- 10 ml tubes (Sarstedt AG, catalog number: 62.9924.284 )

- 2 ml soft sterile bulb transfer pipette, sterile (Stephen Gould corporation, catalog number: 222-1S )

Note: Currently, it is “Capitol Scientific, catalog number: 222-1S”. - 20 µm filter (Sartorius Stedim Biotec, Minisart, catalog number: 16534-K )

- 24-well plate (Corning, Falcon®, catalog number: 353047 )

- Microfuge tubes

- 20 ml syringes

- 0.2 µm filter

- Human umbilical cord blood (40-250 ml)

- 20x Dulbecco’s phosphate buffered (DPBS) (Life Technologies, Gibco®, catalog number: 14200-075 )

Note: Currently, it is “Thermo Fisher Scientific, GibcoTM, catalog number: 14200-075”. - Sterile water (Baxter, catalog number: UKF7114 )

- LymphoprepTM (Axis-Shield, catalog number: 114547 )

- CD133 microbeads including human FcR blocking reagent (Miltenyi Biotec, catalog number: 130-050-801 )

- AutoMACS Pro Washing Solution (Miltenyi Biotec, catalog number: 130-092-987 )

- AutoMACS Running Buffer (Miltenyi Biotec, catalog number: 130-091-221 )

Note: If the AutoMACS Pro separator is not available, cells of interest can be isolated by manual sorting (see below). This manual method, however, is not necessarily optimal for naEFC cell sorting with lower cell viability and number observed; thus the AutoMACS method is preferred. - Endothelial growth media with Bullet kit (EGM-2) (Lonza, catalog number: cc-3162 )

- Fetal bovine serum, characterized (FBS) (VWR International, HycloneTM, catalog number: SH30071.03 )

- Recombinant human Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog number: V7259 )

- Recombinant human Insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-I) (R&D Systems, catalog number: 291-G1-200 )

- Recombinant human fibroblast growth factor basic (FGFb) (R&D Systems, catalog number: 233-FB-025 )

- L-Ascorbic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog number: A5960 )

- Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog number: A6003 )

- EDTA (Merck Millipore Corporation, catalog number: 1.08418 )

- Medium 199 (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog number: M4530 )

- Sodium bicarbonate (7.5%) (Life Technologies, Gibco, catalog number: 25080-094 )

Note: Currently, it is “Thermo Fisher Scientific, GibcoTM, catalog number: 25080-094 ”. - HEPES (1 M) (Life Technologies, Gibco, catalog number: 15630-080 )

Note: Currently, it is “Thermo Fisher Scientific, GibcoTM, catalog number: 15630-080”. - Pen Strep 100x (Life Technologies, Gibco, catalog number: 15140-122 )

Note: Currently, it is “Thermo Fisher Scientific, GibcoTM, catalog number: 15140-122”. - MEM Non-essential amino acid solution 100x (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog number: M7145 )

- Sodium pyruvate 100 mM (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog number: S8636-100 )

- GlutaMAXTM 100x (Life Technologies, Gibco, catalog number: 35050-061 )

Note: Currently, it is “Thermo Fisher Scientific, GibcoTM, catalog number: 35050-061”. - Acetic acid, glacial (Chem Supply, catalog number: AA009-2.5 L )

- Crystal violet (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog number: C3886-25 g )

- 1x DPBS (see Recipes)

- 0.1% BSA/DPBS (see Recipes)

- EGM-2 Media with bullet kit (see Recipes)

- White blood cell counting fluid (see Recipes)

- Fibronectin (Roche Diagnostics, catalog number: 10838039001 ) (see Recipes)

- VEGF (see Recipes)

- FGFb (see Recipes)

- Ascorbic acid (see Recipes)

- IGF-I (see Recipes)

- HUVE media + 20% FBS (see Recipes)

- EGM-2 Media + FBS and growth factors (see Recipes)

- MACS buffer (see Recipes)

Equipment

- Certified biological safety cabinet

- AutoMacs® Pro with chill 15 rack (Miltenyi Biotec, catalog number: 130-092-545 )

- Pipettes

- Pipette gun with ability to set to slow

- Centrifuge with lids (Eppendorf AG, model: 5810R ) with A-4-81 rotor

- Cell counting device (i.e., Haemocytometer)

- Microscope

- CO2 incubator

For manual cell sorting - MiniMACSTM separator (Miltenyi Biotec, catalog number: 130-042-102 )

- MACS MultiStand separator (Miltenyi Biotec, catalog number: 130-042-303 )

Procedure

- Cell Isolation

Note:The AutoMacs® automatic cell sorting is the preferred method for isolating naEFCs however a manual method using the MS columns has also been included if an AutoMacs® is not accessible.

AutoMacs® automatic cell sorting- Collect 40-250 ml of human cord blood from the umbilical vein of placentas from healthy pregnant women, preferably from caesarean section, into cord blood collection bags.

- Transfer cord blood into 50 ml tubes by cutting the tube of the collection bag and draining 25 ml of blood directly into each tube (note 20 ml of this volume is due to the anticoagulant in the collection bags).

- Dilute blood 1:1 with sterile DPBS and mix by inverting the tubes 3-4 times.

- In fresh 50 ml tubes add 15 ml of lymphoprepTM (use 15 ml of lymphoprepTM regardless of blood volume in tube).

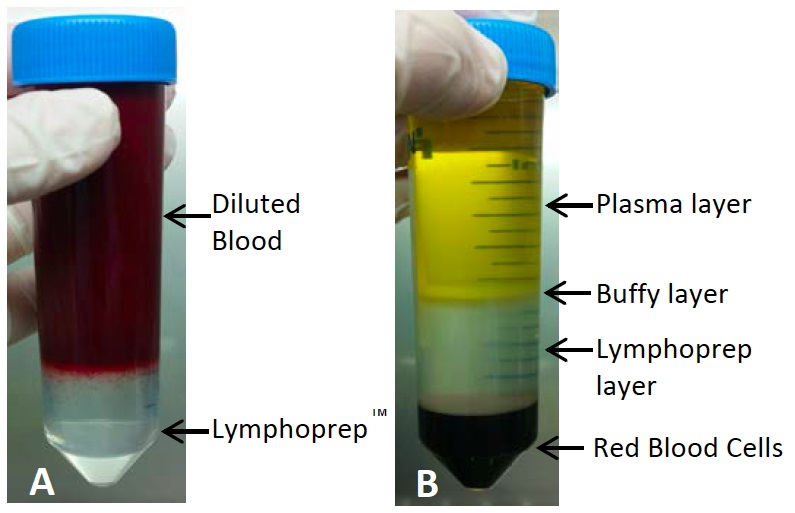

- Carefully layer 35 ml of the diluted blood onto the lymphoprepTM using a 25 ml pipette with the pipette gun set to slow. Do this very slowly so the layer of blood and the layer of lymphoprepTM do not mix (see Figure 3). Repeat until all the diluted blood is layered onto lymphoprepTM in tubes. Minimise the time the blood remains on the lymphoprepTM.

Figure 3. Before and after density centrifugation to separate mononuclear cells. As seen in (A) blood is layered on top of the lymphoprepTM carefully to avoid mixing. Red blood cells can be seen starting to settle down. (B) shows the expected layers following density centrifugation. The buffy layer containing the mononuclear cells is then taken for cell sorting. It is not unusual for cord blood samples to have red blood cells contamination in the buffy layer, have a chunky appearance to the buffy layer or for the plasma layer to appear red from lysed red blood cells, this is all normal. - Immediately centrifuge at 700 x g for 20 min at room temperature with both the brake and acceleration turned to zero to allow the mononuclear cells (MNCs) to separate.

- After centrifugation, the MNCs should be visible as a buffy coat at the interphase between the lymphoprep and the plasma/DPBS layer (see Figure 3).

- Carefully collect the MNCs using a soft sterile bulb transfer pipette by slowly sucking up the buffy layer of cells and transferring the cells to a clean 50 ml tube (this may require multiple tubes it there is a large sample of blood with multiple lymphoprepTM tubes).

- Repeat transfer until no buffy coat remains in each lymphoprepTM tube.

- Dilute transferred buffy coat cells 1:1 with HUVE media in 50 ml tube/s.

- Centrifuge at 450 x g for 5 min at room temperature.

- Aspirate the supernatant, resuspend cells in 10 ml of HUVE media.

- Combine cells into one 50 ml tube, if required.

- Take a sample for cell counting to determine total cell number. Counting a range of 50-250 cells to calculate cell number should give an accurate enough result for this stage of the protocol, an appropriate volume and dilution to achieve this range may need to be worked out.

- Dilute cells 1:1 (as a minimum dilution) with the white blood cell counting fluid. Leave mix for 2 min so red blood cells can lyse for a more accurate cell count. All nucleated cells will appear blue for counting on a haemocytometer or equivalent. Count cells and determine total cell number.

- Wash cells twice more by resuspending in 25 ml HUVE media followed by centrifugation at 450 x g for 5 min at room temperature. When aspirating supernatant do not remove all media from the pellet before resuspension to improve cell yield.

- Aspirate supernatant and resuspend ≤ 1 x 108 cells in 500 μl of HUVE media by pipetting up and down slowly and transfer to a 10 ml tube (if there is more than 1 x 108 cells add 1 ml of HUVE media and split into 2 tubes and continue for each tube).

- Add 100 μl of human FcR blocking reagent followed by 100 μl of resuspended CD133 microbeads and mix well. Incubate for 30 min at 4 °C in the dark.

- Centrifuge tubes at 4 °C at 450 x g for 5 min (for manual cell sorting proceed to protocol below).

- Meanwhile turn on AutoMACS® Pro and attach running buffer and perform rinse cycle as per manufacturer’s instructions.

- Aspirate supernatant carefully and resuspend cells in 3 ml sterile MACS buffer by gently pipetting up and down.

- On the AutoMACS® Pro select “possel-s” (positive selection-sensitive) and set the desired number of samples as per manufacturer’s instructions.

- Use chilled AutoMACS® Chill 15 rack and insert sample tube with cells into position 1 and empty 10 ml tubes into position 2 (CD133 negative) and 3 (CD133 positive). Run program.

- Combine all CD133 positively sorted cells and perform a cell count with the white blood cell counting fluid as per step 15 to determine media volume for seeding.

- Centrifuge at 450 x g for 5 min at room temperature.

For manual cell sorting- Attach miniMACSTM magnetic separator to the MultiStand and insert an MS column (1 per sample) into the separator and place a collection tube under the column (this can be seen in the manufacturer's product information sheet).

- To prepare column, add 500 μl MACS buffer to the top of the column and allow to flow through the column (it will not run dry). Discard flow through from collection tube.

- Aspirate supernatant (from step A19) carefully and resuspend cells in 1 ml sterile MACS buffer by gently pipetting up and down.

- Add the cell suspension to the top of the column 500 μl at a time. Unlabelled cells will flow through into the collection tube.

- Wash the column by adding 500 μl of MACS buffer to the column. Repeat 3 times.

- Remove the MS column from the separator and place on a new collection tube.

- Add 1 ml of MACS buffer to the column and using the plunger supplied with the column, immediately flush out positively labelled cells by firmly pushing the plunger down the column.

- Proceed to step A24.

- Collect 40-250 ml of human cord blood from the umbilical vein of placentas from healthy pregnant women, preferably from caesarean section, into cord blood collection bags.

- Initial cell seeding

- Coat a 24 well plate with 300 µl of fibronectin for each well (about 1-6 wells will be required depending on sample size) and leave well plate for at least 30 min in a 5% CO2 incubator set to 37 °C.

- Make up required amount of EGM-2 media with growth factors.

- Resuspend CD133+ cells at a density of 1 x 106 cells/ml in EGM-2 with growth factors.

- Aspirate the fibronectin from the wells, no additional washing is required.

- Add cells to the well/s (1-2 ml per well).

- Place well plate into a 5% CO2 incubator set to 37 °C this is considered as day 0.

- Coat a 24 well plate with 300 µl of fibronectin for each well (about 1-6 wells will be required depending on sample size) and leave well plate for at least 30 min in a 5% CO2 incubator set to 37 °C.

- Cell culture (separating non-adherent and adherent cells)

- After 48 h (day 2) from initial seeding, cells need to be transferred to a new fibronectin coated well to separate the desired non-adherent cells from the small number of adherent cells.

- Coat new a 24 well plate with 300 µl of fibronectin for each well leave well plate for at least 30 min in a 5% CO2 incubator set to 37 °C.

- Separate non-adherent cells by collecting all non-adherent cells from all wells into a 10 ml tube.

- Wash all wells with 1 ml per well of DPBS by pipetting gently up and down in each well and add to the tube of non-adherent cells.

- Centrifuge at 450 x g for 5 min at room temperature.

- Aspirate supernatant carefully to avoid sucking up any of the cell pellet and resuspend cells in fresh EGM-2 with growth factors at a density of 1 x 106 cells/ml.

- Aspirate the fibronectin from the wells (no additional washing is required) and add cells (1-2 ml per well) to the newly fibronectin coated well/s.

- Place well plate into a 5% CO2 incubator set to 37 °C until day 4-5 when a homogeneous population of cells is formed (see Figure 2 for examples of the cell population at this stage).

- After 48 h (day 2) from initial seeding, cells need to be transferred to a new fibronectin coated well to separate the desired non-adherent cells from the small number of adherent cells.

Notes

- All procedures aside from blood collection and AutoMacs® Pro cell sorting should be performed under sterile conditions in a certified biological safety cabinet using aseptic technique.

- Relevant human ethics for human cord blood collection and research use needs to be in place prior to collection.

- There is extensive donor variation in both overall mononuclear cell and CD133 positive cell numbers and some samples appear a lot darker or thicker than others. For example, you might have a higher cell yield from a smaller volume of blood compared to a different sample. From 40-250 ml of blood the expected CD133 positive cell yield would be from 5 x 105 to 8 x 106 cells. Ideally the largest volume of blood should be collected but this if often limited by donors and birthing techniques as cord blood collection should not compromise the health of the donor.

- Blood can be collected and left at room temperature overnight in the collection bag at room temperature on a rocker but cell numbers recovered may be lower.

- Do not do a specific red blood cell lysis step as it affects the naEFCs viability. The slight RBC and other cell contamination seemingly help cell viability and the CD133+ cells become homogeneous after 4 days in the selective media.

Recipes

- 1x DPBS

Dilute 20x DPBS 1:20 in sterile water to get 1x DPBS - 0.1% BSA/DPBSDissolve BSA into DPBS and then sterilise through a 0.2 µm filter

DPBS 100 ml BSA 0.1 g - EGM-2 Media with bullet kit

As per manufacturer’s instructions, add all components of the bullet kit to the EBM-2 media bottle to make the EGM-2 media

Aliquot and store at -20 °C until use - White blood cell counting fluidDissolve and mixing well then sterilise with a 0.2 µm filter

Acetic acid, glacial 1 ml Water 49 ml Crystal violet 7.5 mg

Stored at room temperature

Dilute cells into this preparation and count with hemocytometer - Fibronectin

Reconstitute with sterile water to make 1 mg/ml and leave at 37 °C for 30-60 min to dissolve without agitation

Store stock at -20 °C

Dilute 1 mg/ml stock to 50 mg/ml in sterile DPBS for use

Stored at 4 °C - VEGF

Reconstitute to 5 µg/ml in sterile 0.1% BSA/DPBS

Aliquot and stored at -20 °C - FGFb

Reconstitute to 25 µg/ml in sterile 0.1% BSA/DPBS

Aliquot and stored at -80 °C - Ascorbic acid

Reconstitute to 0.5 M in sterile water

Aliquot and stored at -20 °C - IGF-I

Reconstitute to 100 µg/ml in sterile DPBS

Dilute to 5 µg/ml in sterile DPBS

Aliquot and stored at -80 °C - HUVE media + 20% FBS

Medium 199 400 ml Fetal bovine serum 100 ml 1 M HEPES 10 ml 7.5% sodium bicarbonate 7.5 ml 100x GlutaMAXTM 5 ml 100x MEM Non-essential amino acid solution 5 ml 100x Pen strep 5 ml 100 mM sodium pyruvate 5 ml - EGM-2 media + FBS and growth factors

Table 1. EGM-2 Media, FBS and Growth Factors recipeDilution To make 5 ml Final concentration EGM-2 media with Bullet kit added 4.5 ml Fetal bovine serum (1/10) 500 μl 10% VEGF (5 µg/ml) (1/1,000) 5 μl 5 ng/ml IGF-1 (5 µg/ml) (1/5,000) 1 μl 1 ng/ml Ascorbic acid (0.5 M) (1/5,000) 1 μl 0.1mM bFGF (25 µg/ml) (1/25,000) 10 μl 1 ng/ml

0.2 µm sterile filter and use immediately - MACS buffer

100 ml 1x DPBS

0.5 g BSA (0.5%)

0.074 g EDTA (2 mM)

pH 7.2

0.2 µm sterile filter

Stored at 4 °C

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Sarah Appleby, Dr. Katie Tooley, Dr. Jeffrey Barrett and Samantha Escarbe for their assistance in developing this protocol; Dr. Rosalie Grivell, the staff and consenting donors at Women’s and Children’s Hospital and Burnside Memorial Hospital for collection of the umbilical cord blood. This project was funded by a Heart Foundation Fellowship to CSB (CR10A4983) as well as a project grant from the Co-operative Research Centre for Biomarker Translation (Trans Bio Ltd).

References

- Appleby, S. L., Cockshell, M. P., Pippal, J. B., Thompson, E. J., Barrett, J. M., Tooley, K., Sen, S., Sun, W. Y., Grose, R., Nicholson, I., Levina, V., Cooke, I., Talbo, G., Lopez, A. F. and Bonder, C. S. (2012). Characterization of a distinct population of circulating human non-adherent endothelial forming cells and their recruitment via intercellular adhesion molecule-3. PLoS One 7(11): e46996.

- Barrett, J. M., Parham, K. A., Pippal, J. B., Cockshell, M. P., Moretti, P. A., Brice, S. L., Pitson, S. M. and Bonder, C. S. (2011). Over-expression of sphingosine kinase-1 enhances a progenitor phenotype in human endothelial cells. Microcirculation 18(7): 583-597.

- Moldenhauer, L. M., Cockshell, M. P., Frost, L., Parham, K. A., Tvorogov, D., Tan, L. Y., Ebert, L. M., Tooley, K., Worthley, S., Lopez, A. F. and Bonder, C. S. (2015). Interleukin-3 greatly expands non-adherent endothelial forming cells with pro-angiogenic properties. Stem Cell Res 14(3): 380-395.

- Parham, K. A., Zebol, J. R., Tooley, K. L., Sun, W. Y., Moldenhauer, L. M., Cockshell, M. P., Gliddon, B. L., Moretti, P. A., Tigyi, G., Pitson, S. M. and Bonder, C. S. (2015). Sphingosine 1-phosphate is a ligand for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma that regulates neoangiogenesis. FASEB J 29(9): 3638-3653.

Article Information

Copyright

© 2016 The Authors; exclusive licensee Bio-protocol LLC.

How to cite

Cockshell, M. P. and Bonder, C. S. (2016). Isolation and Culture of Human CD133+ Non-adherent Endothelial Forming Cells. Bio-protocol 6(7): e1772. DOI: 10.21769/BioProtoc.1772.

Category

Stem Cell > Adult stem cell > Epithelial stem cell

Cell Biology > Cell isolation and culture > Cell isolation

Do you have any questions about this protocol?

Post your question to gather feedback from the community. We will also invite the authors of this article to respond.

Share

Bluesky

X

Copy link